On CBT, false consciousness, and social progress

Thursday, April 6, 2023

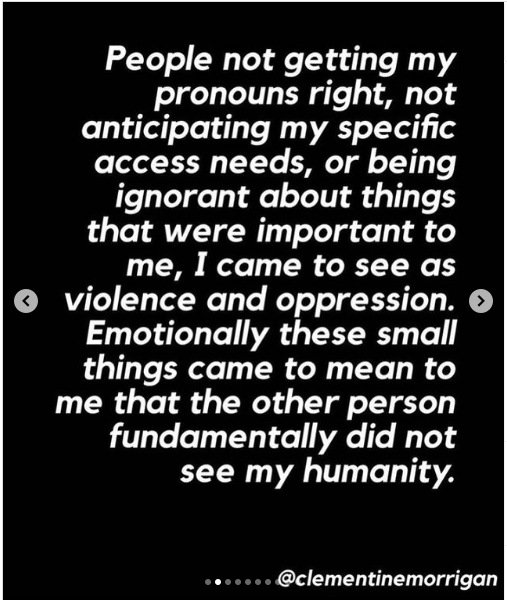

Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff argue that the mental habits of young progressives amount to “reverse CBT”, that emotional reasoning, black-and-white thinking, and catastrophizing are endemic.1 Clementine Morrigan says that social justice culture encouraged her “to see the actions of others in the worst possible light, to take things extremely personally”.2 These observations echo the experiences of many leftists that I know and, as well as worsening mental health, make people worse at discerning the most pressing political issues. To fully explain this phenomenon I think we have to situate it historically; in particular, we have to look at second-wave feminist approaches to movement building.

“False consciousness” is a Marxist concept, describing the state of oppressed people who don’t know that they’re oppressed. Second-wave feminists in the 60s popularised “consciousness raising” groups as a wellspring of political activism (note that “woke” and, on the other side of the political spectrum, “red-pilled” are also variations on this metaphor). The idea behind these groups was that when women get together to share their experiences they develop “the idea of doing something politically about aspects of our lives as women that we never thought could be dealt with politically, that we thought we would just have to work out as best we could alone.”3 A key feminist slogan of the same era was “the personal is political”, and this informed the approach: “We assume that our feelings are telling us something from which we can learn… that our feelings are saying something political…”3

Second-wave feminism was hugely productive, securing numerous legal victories (on equal pay, anti-discrimination, divorce law, abortion law, etc.), opening the first rape and domestic violence services, and overhauling social attitudes towards women.4 Frankly, there was a lot of low-hanging fruit. If you got a group of women together in the 60s to analyse their lives, you would quickly converge on some really significant sex-based injustices. At that point in history, consciousness raising helped women to identify and thereby organise against their systemic oppression and disenfranchisement.

Another illustration of consciousness raising, from Martha Nussbaum: “In the semi-arid area outside Mahabubnagar, Andhra Pradesh, I talked with women who were severely malnourished, and whose village had no reliable clean water supply. Before the arrival of a government consciousness-raising program, these women apparently had no feeling of anger or protest about their physical situation. They knew no other way. They did not consider their conditions unhealthy or unsanitary, and they did not consider themselves to be malnourished. Now their level of discontent has gone way up: they protest to the local government, asking for clean water, for electricity, for a health visitor.”5

Is consciousness raising “reverse CBT”? The premise of CBT, which has its origins in Stoic philosophy, is that we can interrogate feelings using reason and evidence. CBT teaches people to recognise common cognitive distortions that worsen mental health, while consciousness raising teaches people to recognise structural features of society that impact their lives. In a way, they have a lot in common: both encourage the adoption of a more accurate worldview and resultant attitudinal tuning. The apparent tension arises because the latter tends to address magnification (the exaggeration of negatives), the former minimisation. The risk in both cases is that you overcorrect.6

To say that contemporary Western progressives are overcorrecting is of course to beg the question to some degree. But it is telling that so much discourse revolves around microaggressions: by definition, very minor harms. The personal can be political, but this is not to say that we ought to politicise (and problematise) every interaction that we have. The teachings of second-wave feminists (and other radical civil rights activists of that era) have been fully assimilated into progressive thought without appreciation of the changing context. All the gains of the last 50 years were for nothing if women today feel just as oppressed as they ever were; clearly, that isn’t the case.

Beverly Jones wrote in 1968 that “[y]ou don’t get radicalised fighting other people’s battles”.7 Movement building was based on encouraging all women to see themselves as victims of sex-based oppression. It’s easy to see how these exhortations have influenced the tendencies in social justice culture to “take things extremely personally”: if we agree with Beverly Jones, our only options are to leave the most marginalised groups to fight their own battles, or persuade more people to see themselves as victims.8 But manufacturing victimisation where there is none does damage not only to individual mental health but also to political thought; far better to appreciate your own agency and put it to use on the most pressing causes.

- Why the Mental Health of Liberal Girls Sank First and Fastest

- Clementine Morrigan on Instagram

- Kathie Sarachild in Feminist Revolution

- 1970s Feminism Timeline

- Adaptive Preferences and Women’s Options

- There is a misperception that the Stoic locus of change is always internal, but in fact Stoics have always taken a view on politics. See, e.g, The Ideal Polity of the Early Stoics

- Towards a Female Liberation Movement

- I find it a little ironic that so many radical thinkers, typically opposed to capitalism, endorse a version of the economists’ creed that people act in their own self-interest.